“I can’t stand to sing the same song the same way two nights in succession, let alone two years or ten years. If you can, it ain’t music, it’s close order drill or exercise or yodeling or something, not music.” – Billie Holiday

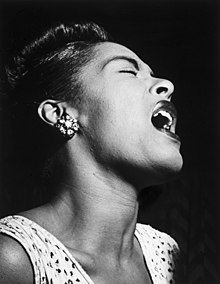

Billie Holiday in full flight (image courtesy Wikimedia)

Lady Sings the Blues is, I suppose, one of the first autobiographies by a popular music star. This, the first book from the 2017 reading list, is an “as told to.” One of the things the ghost writer (to resurrect an old term), William Dufty, a reporter for the New York Post and a personal friend of Holiday does beautifully is avoid much revision of Holiday’s words. As best as I have been able to discover, Dufty did a series of extended interviews with Holiday without the benefit of tape recording. That Lady Sings the Blues reads like a transcribed conversation with Lady Day is a tribute to Dufty’s careful rendering of Holiday’s words in her voice.

Dufty’s success in allowing Holiday to speak for herself is both charming and haunting, both illuminating and (unintentionally, perhaps) misleading. What one realizes as one reads this autobiography is that Holiday’s goal is to reveal herself without giving herself away. Let me put that more accurately: what Billie Holiday tries to do in Lady Sings the Blues is not give her self away even as she reveals herself.

In others words, like the rest of us, Billie Holiday is willing to tell us only so much.

Holiday’s story (her real name was Eleanora Fagan; Billie Holiday, her stage name, was a compendium of the first name of a favorite actress, Billie Dove, and the last name of her father, Clarence Holiday, a jazz musician who abandoned Holiday and her mother without marrying Billie’s mother, Sadie) is divided into three identifiable streams that flow through her life: the story of her miserable childhood, the story of her rise to stardom as a jazz and blues singer, and the story of her drug addiction.

The stream of Holiday’s childhood contains enough dirty flotsam to have supported any psychiatry practice: she spent much of her childhood shunted between her mercurial, nomadic mother (who gave birth to Billie when only 13 and who worked railroad jobs that involved constant travel) and her stern, disapproving aunt who bullied and tormented her. Her father was an absent figure, and one senses that her wayward youth (she joined her mother in practicing prostitution when she was 14) and later troubles with men likely flowed from a desire to be loved and appreciated that this miserable childhood bestowed.

As is the case with many stars, Holiday found her love and acceptance through her talent. Her careerand began in small clubs in Harlem when she was still a teenager (after a short stint in a women’s correctional institution for prostitution) brought her to the attention of Benny Goodman. From that connection came her discovery by legendary music producer John Hammond who helped her gain recording contracts. Working with top artists such as Teddy Wilson, Count Basie, and Artie Shaw, Holiday became both a successful recording and performing singer rivaling even Ella Fitzgerald as the most popular (sadly, I must qualify) black singer of the period of the thirties and forties. I mention Holiday’s race because race is a persistent theme in Lady Sings the Blues; Holiday discusses the topic at length, particularly in her recollections of the racist treatment she received while touring with Artie Shaw’s band (she was the only black performer). I mention this because it gets at an issue that explains some of Holiday’s negative behaviors: despite her stardom, she was still treated as a second-hand citizen, a cognitive dissonance she never really resolved. One might say that while her talent in part made her a star, the drive she needed to succeed came from that desire to be loved and appreciated that flowed from her difficult childhood. The racism she encountered undercut the love and acceptance her talent and stardom gave her….

Perhaps that explains the third stream that ran through Billie Holiday’s life, her drug addiction. Holiday herself is vague about when she actually began to use heroin, though biographers describe her association with jazz trumpeter Joe Guy which began in the early 1940’s as the staring point. Why she began, as I have noted above, may stem from the other streams of her life: the difficulty and misery of her childhood, the racism she encountered even as an established musical star, and her bad taste in men. Maybe heroin became an escape from the stresses of her career and the disappointment she felt as being seen (and demeaned) as a black person even though she was a celebrated singing star. Whatever the genesis of her addiction, this stream, the stream of addiction, became the one that bore her away – away from her stardom, away from her freedom (she did jail time and was arrested on multiple occasions) eventually away from her life. She died of complications of cirrhosis of the liver at 44.

Holiday’s musical legacy is secure, although she might be distressed that her talent and stardom is always seen in light of her tragic personal life. In recounting an anecdote about yet another racist whose inconsistent behavior in a moment of crisis (on board a plane that had an engine fire but which landed safely), Billie Holiday offers a comment that in an ironic way sums up her own brilliant career and sad life:

…you’ve had your lesson today. Some people is and some people ain’t, and this [one] ain’t.

And that is the real tragedy of Lady Day – she could never decide if she was or she wasn’t.

Pingback: Dancing about architecture: trying to read Paul Morley’s Words and Music… | The New Southern Gentleman

Pingback: Dancing about architecture: trying to read Paul Morley’s Words and Music… | Progressive Culture | Scholars & Rogues